Deconstructing the Past: Rethinking History and Its Narratives

Deconstruction and postcolonialism have significantly influenced the ways in which historians engage with the past, particularly in relation to the writing of history and the interrogation of historical narratives. Deconstruction, as introduced by Jacques Derrida, questions the very foundation of meaning, arguing that language and texts do not possess fixed meanings but instead generate endless chains of signification. When applied to history, deconstruction reveals that historical narratives are not neutral....

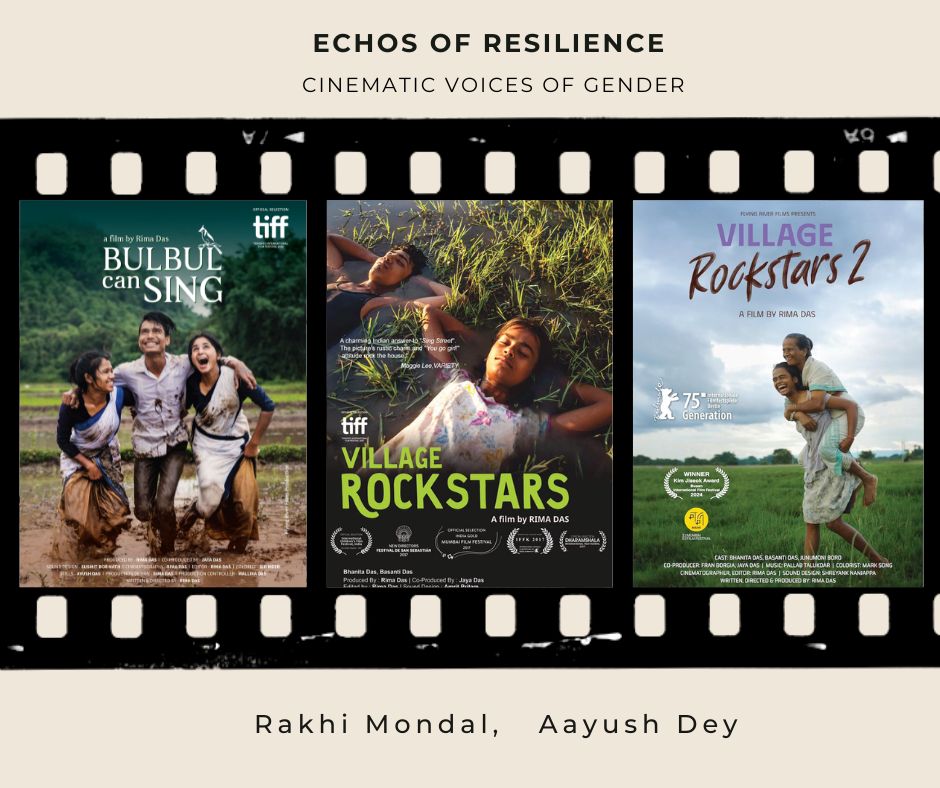

Echos of Resilience : Cinematic Voices of Gender

Films are a vital cultural artifact that offer a lens through which historians, theorists, and feminist scholars can explore the societal, political, and ideological landscapes of their time. Far from being mere entertainment, films encapsulate social norms, power dynamics, and cultural values, reflecting and shaping public consciousness. The study of films as historical and cultural sources has gained significant academic traction, especially in the fields of feminist and postcolonial studies, where cinema is scrutinized....

Deconstructing the Past: Rethinking History and Its Narratives

Deconstruction and postcolonialism have significantly influenced the ways in which historians engage with the past, particularly in relation to the writing of history and the interrogation of historical narratives. Deconstruction, as introduced by Jacques Derrida, questions the very foundation of meaning, arguing that language and texts do not possess fixed meanings but instead generate endless chains of signification. When applied to history, deconstruction reveals that historical narratives are not neutral or objective accounts of the past but are constructed within ideological frameworks, shaped by the biases and power structures of those who produce them. Postcolonialism, on the other hand, builds upon this critique by emphasizing the role of colonialism in shaping historical knowledge, highlighting the erasure of subaltern voices, and contesting Eurocentric interpretations of non-European pasts. One of the most crucial implications of deconstruction in historical studies is its challenge to the idea of a singular, authoritative history. Traditionally, history has been written with an assumption of linearity and factual accuracy, often privileging written records over oral traditions and other alternative sources of knowledge. Derrida’s concept of différance, which suggests that meaning is always deferred and never fully present, applies to historical narratives as well, indicating that no historical account is ever complete or final. This is particularly evident in the historiography of medieval India, where the dominant narratives have often been constructed within colonial, nationalist, or religious frameworks, each interpreting the past in ways that serve their respective ideological agendas. A striking example can be found in the colonial historiography of medieval India, particularly in British narratives that framed the period as an era of "Muslim despotism" preceding the "civilized" British rule. Historians such as James Mill, in his History of British India (1817), divided Indian history into Hindu, Muslim, and British periods, reinforcing a binary that has had lasting implications for communal historiography. This categorization imposed a rigid and teleological structure on Indian history, portraying Muslim rulers as tyrannical oppressors and Hindu subjects as passive victims awaiting salvation through British governance. Deconstruction allows historians to challenge such imposed binaries, revealing the underlying biases and inconsistencies within these colonial constructions. A deconstructive reading of Mughal rule, for instance, would expose how figures like Akbar, often categorized as a benevolent exception among so-called despotic rulers, are framed within narratives that ignore the complexities of governance, administrative structures, and cultural synthesis. Postcolonialism further deepens this critique by analyzing how colonial narratives erased indigenous perspectives and subaltern voices. Edward Said’s Orientalism (1978) demonstrated how European scholars constructed an image of the East as an exotic, backward, and irrational "Other," which justified colonial domination. This framework was evident in the writings of colonial historians like Vincent Smith, whose portrayal of medieval India emphasized religious conflicts and dynastic rivalries while downplaying economic structures, social mobility, and indigenous agency. The postcolonial intervention in historical studies, especially through the works of the Subaltern Studies collective, has sought to recover these marginalized voices by challenging elite-centered historiography. Ranajit Guha and his colleagues argued that colonial and nationalist histories alike tended to focus on rulers, elite political figures, and state institutions, neglecting the agency of peasants, artisans, and tribal communities in shaping historical events. A crucial example of postcolonial historiography in medieval Indian studies is the re-examination of peasant uprisings and tribal resistance, which were often dismissed in colonial accounts as mere "disturbances" rather than legitimate political actions. The study of the Santhal Rebellion (1855-56) or the Kol Revolt (1831-32) through a postcolonial lens challenges the colonial categorization of these events as sporadic outbursts, instead interpreting them as complex struggles against economic exploitation and dispossession. Similarly, postcolonial historians have problematized the representation of the Bhakti and Sufi movements, which colonial historiography often reduced to either purely religious phenomena or as evidence of syncretism. In reality, these movements were also deeply entangled with caste, class, and gender dynamics, resisting Brahmanical hegemony and creating alternative spaces for marginalized groups. Gayatri Spivak’s famous essay Can the Subaltern Speak? (1988) further complicates the question of historical representation by arguing that even attempts to recover subaltern voices are often mediated by elite frameworks, making it difficult for the subaltern to truly "speak" within dominant historiographical traditions. This is particularly relevant when examining the position of women in medieval Indian history. Traditional historiography has often depicted women either as passive victims of patriarchal structures or as exceptional figures such as queens and courtesans, without accounting for the ways in which everyday women negotiated power and resistance. A postcolonial and deconstructive approach would question the very sources through which medieval women’s histories are constructed, recognizing that courtly chronicles, religious texts, and legal documents often reflect the perspectives of elite men rather than the lived experiences of ordinary women. The historiography of the Mughal harem is a particularly fertile ground for such an analysis. Colonial and nationalist narratives alike have tended to exoticize the harem as a site of decadence and sensuality, reducing the women within it to objects of desire rather than active participants in court politics. Recent scholarship, however, influenced by feminist and postcolonial methodologies, has attempted to reconstruct the agency of women in the Mughal court, emphasizing their roles as political advisors, patrons of art, and key figures in succession disputes. Ruby Lal’s work on Mughal women, for instance, deconstructs the colonial portrayal of the harem by examining it as a complex socio-political institution rather than a space of passive seclusion. Homi Bhabha’s concept of "hybridity" further complicates historical narratives by highlighting the cultural and linguistic exchanges that occurred under colonial and pre-colonial rule. Medieval India, particularly under the Delhi Sultanate and the Mughal Empire, witnessed the blending of Persianate, Indic, and Turkic traditions, resulting in new political and cultural formations. A rigid nationalist historiography, whether Hindu or Muslim, often ignores these hybridities in favor of constructing a homogenous past. Bhabha’s notion of the "third space" suggests that cultural identities are not fixed but are constantly negotiated and redefined. This perspective challenges the communal historiographies that attempt to essentialize religious identities in medieval India, instead revealing how syncretic traditions like Indo-Persian literature, Sufi-Bhakti interactions, and architectural innovations emerged from cross-cultural exchanges. Deconstruction and postcolonialism together encourage historians to move beyond simplistic dichotomies and to recognize history as a contested field of knowledge production. The challenge lies not only in rewriting history but also in critically examining the frameworks through which history itself is written. Whether it is the colonial portrayal of medieval India as a period of stagnation, the nationalist attempts to reclaim a glorious past, or the subaltern struggles against historical erasure, these theoretical approaches remind us that history is not a fixed narrative but an ongoing process of negotiation, reinterpretation, and resistance. The role of the historian, therefore, is not just to uncover the past but to interrogate the very structures that determine how the past is remembered and represented.

Bibliography

1. Bhabha, Homi K. The Location of Culture. Routledge, 1994.

2. Chakrabarty, Dipesh. Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference. Princeton University Press, 2000.

3. Derrida, Jacques. Of Grammatology. Translated by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1976.

4. Derrida, Jacques. Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression. Translated by Eric Prenowitz, University of Chicago Press, 1995.

5. Guha, Ranajit. Dominance without Hegemony: History and Power in Colonial India. Harvard University Press, 1997.

6. Guha, Ranajit, and the Subaltern Studies Collective. Subaltern Studies I-XII. Oxford University Press, 1982-2005.

7. Lal, Ruby. Domesticity and Power in the Early Mughal World. Cambridge University Press, 2005.

8. Mill, James. The History of British India. Baldwin, Cradock, and Joy, 1817.

9. Said, Edward W. Orientalism. Pantheon Books, 1978.

10. Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. Can the Subaltern Speak? In Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, edited by Cary Nelson and Lawrence Grossberg, University of Illinois Press, 1988.

11. Smith, Vincent A. The Oxford History of India. Oxford University Press, 1919.

12. Thapar, Romila. The Past as Present: Forging Contemporary Identities through History. Aleph, 2014.

13. Trouillot, Michel-Rolph. Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History. Beacon Press, 1995.

Echos of Resilience : Cinematic Voices of Gender

Written by : Rakhi Mondal, Aayush Dey

Films are a vital cultural artifact that offer a lens through which historians, theorists, and feminist scholars can explore the societal, political, and ideological landscapes of their time. Far from being mere entertainment, films encapsulate social norms, power dynamics, and cultural values, reflecting and shaping public consciousness. The study of films as historical and cultural sources has gained significant academic traction, especially in the fields of feminist and postcolonial studies, where cinema is scrutinized for its representation of marginalized voices, including women.

In positioning my work as a new contribution to film studies, it is crucial to highlight the existing gap in scholarly literature on the representation of women and queer identities in Assamese cinema. Previous research on regional Indian cinema, including Assamese films, has largely focused on socio-political contexts, ethnic identity, and cultural preservation, as seen in studies by Bhattacharjee (2015) and Barua (2017), who emphasize Assamese cinema’s role in reflecting local narratives and ethnic consciousness. While there has been an analysis of gendered representation in classic Assamese films like Joymoti, there has been minimal application of feminist and queer theory to contemporary Assamese films, particularly in works such as Village Rockstar and Bulbul Can Sing.

This gap is particularly evident in the absence of feminist theoretical frameworks, such as those by Judith Butler and Laura Mulvey, in studying female agency and queer subtexts in Assamese cinema. My research thus provides a critical intervention by applying these theories to explore how these films challenge patriarchal and heteronormative narratives that have traditionally dominated Assamese cultural productions. Moreover, no existing study addresses the intersection of feminist and queer theory within this regional context, a gap that my work directly addresses by positioning Village Rockstar and Bulbul Can Sing as pioneering texts in reshaping Assamese cinema’s portrayal of marginalized identities. By doing so, this study not only adds a significant layer of understanding to Assamese cinema but also broadens the scope of feminist film criticism within Indian regional cinema, ultimately advancing the discourse on gender, identity, and agency in underrepresented cinematic traditions.

Marc Ferro, a pioneering historian in the field of cinema studies, highlights the dual role of films as both mirrors of historical reality and instruments that actively shape that reality. Ferro argues that cinema serves as a valuable historical source because it offers insights not only into the events portrayed but also into the ideologies and power structures that inform them. He writes “Cinema is not only a reflection of the historical period in which it is produced but also an agent that participates in the construction of history itself, influencing social and political attitudes.”

Similarly, Robert A. Rosenstone’s work Visions of the Past explores how films can convey complex historical narratives. He emphasizes that films provide a sensory and emotional engagement with history that is often missing from traditional historical texts. For Rosenstone, films function as “visual histories” that, while not always factually accurate, offer a unique interpretive lens through which viewers can understand societal conditions and cultural discourses of the past.1

Postcolonial theory offers a powerful framework for analysing films, particularly in how they portray the relationship between colonizer and colonized. Edward Said’s foundational work Orientalism critiques how Western cultural representations, including films, have historically constructed the “Orient” as exotic, backward, and inferior.2 This framing can be extended to the portrayal of women in postcolonial societies, where both colonial and patriarchal structures have influenced their representation in cinema.

Postcolonial feminists, such as Gayatri Spivak and Chandra Talpade Mohanty, have argued that films from postcolonial regions often serve as a site for negotiating gender and identity. Spivak’s notion of the “subaltern” is particularly relevant here3, as women in postcolonial films are often depicted in ways that either reinforce or resist their subaltern status. This theoretical framework encourages an examination of how films reflect the intersection of gender, race, and colonial history, often portraying women as both subjects of oppression and agents of resistance.

Antonio Gramsci’s theory of cultural hegemony is central to understanding how films can either reinforce or subvert dominant ideologies. Gramsci suggests that the ruling class maintains control not only through economic and political power but also by shaping cultural and intellectual life. Films, as a form of popular culture, play a significant role in this process, as they propagate dominant worldviews, including patriarchal and capitalist ideologies.

From a feminist perspective, Gramsci’s theory highlights how cinema can perpetuate gendered power dynamics by normalizing patriarchal values. However, it also opens up the possibility for counter-hegemonic narratives. Feminist filmmakers, for instance, can use cinema to challenge the dominant representations of women, offering instead portrayals that emphasize female agency, resistance, and empowerment. By disrupting hegemonic gender norms, films can act as a site of ideological resistance, fostering new ways of understanding and representing women in society.

Michel Foucault’s theories on power and discourse provide another crucial lens through which to analyse films, particularly in relation to gender. Foucault’s understanding of power is not confined to institutions or individuals; rather, he sees power as diffused through networks of discourse that shape how people understand themselves and their world. In this context, films act as a medium through which discourses about gender, sexuality, and identity are produced and circulated.

Foucault’s concept of “the gaze”4 is particularly important in feminist film theory. Scholars like Laura Mulvey have extended his ideas to critique how women are objectified in films through the “male gaze,” where the camera—and by extension, the audience—views women from a male, often voyeuristic, perspective5. This gaze not only objectifies women but also reinforces their subjugation within a patriarchal power structure.

Foucault’s emphasis on power relations is central to feminist critiques of film because it highlights how cinema functions as a tool for producing and reinforcing gendered hierarchies. Films are not neutral; they are embedded within power structures that shape how women are represented and how viewers are encouraged to interpret those representations. This opens the door for feminist filmmakers and critics to challenge these power structures by producing films that resist the male gaze and offer alternative representations of women.

Feminist film theory, particularly the work of scholars like Laura Mulvey, Bell Hooks, and Judith Butler, provides a critical framework for analysing how gender is constructed and represented in cinema. Mulvey’s influential essay (later a book) Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema introduced the concept of the male gaze, arguing that mainstream cinema is structured around a patriarchal view of women, who are portrayed as passive objects for male desire.6 This theory encourages a deeper examination of how films can reinforce traditional gender roles and the ways in which women are denied agency in cinematic narratives.

bell hooks, in her work on Oppositional Gaze, expands this critique by arguing that black women, in particular, have historically been excluded from dominant cinematic representations. She advocates for an "oppositional gaze"7 where marginalized audiences actively resist and critique these portrayals. hooks’ analysis is crucial in exploring how films can simultaneously reflect and challenge intersecting systems of oppression, such as race, class, and gender.

Judith Butler’s theory of gender performativity, which argues that gender is not a fixed identity but rather a performance constructed through repeated social acts, offers another layer of critique.8 In cinema, gendered performances are often codified through costume, behaviour, and narrative arcs, reinforcing normative understandings of masculinity and femininity. However, films that disrupt these performances—by showing women in roles traditionally reserved for men, for example—challenge these norms and create space for alternative forms of gender expression.

Feminist film scholars argue for a radical rethinking of how women are portrayed in cinema. By examining the ways in which films reproduce or resist patriarchal norms, feminist critics can uncover the subtle mechanisms through which gender is constructed and perpetuated. In doing so, they open up new possibilities for films to serve as a site of feminist intervention, where traditional gender roles are not only questioned but also reimagined.

Films are a dynamic and complex medium through which societal norms, power relations, and cultural identities are constructed and contested. The theoretical frameworks provided by postcolonial theory, Gramsci’s concept of cultural hegemony, Foucault’s analysis of power and discourse, and feminist film theory offer powerful tools for analysing how films both reflect and shape the world. By critically engaging with cinema through these lenses, we can explore the intricate ways in which films contribute to the construction of gender, power, and identity, making cinema a rich source for feminist discourse and critique.

Existing scholarship on Assamese cinema has traditionally focused on its cultural and historical narratives, particularly in the works of Rinku Pegu and Rashmi Sarmah, who have examined the representation of women in films like Joymoti. However, despite this scholarly attention to gender, these studies remain constrained by a lack of feminist and queer theoretical engagement with contemporary films such as Village Rockstar and Bulbul Can Sing. This research gap is glaring, given the significant socio-political shifts in Assam, especially concerning gender dynamics and the representation of marginalized identities. The necessity to address this gap becomes even more critical when we consider that both films, while embedded in the cultural fabric of rural Assam, present complex and layered critiques of patriarchal structures and heteronormative expectations, with Bulbul Can Sing subtly weaving in LGBTQ+ themes. This absence of feminist and queer critique in existing literature underscores the urgency of my intervention.

The proposed analysis not only fills a crucial gap in Assamese cinema studies but also challenges the broader academic neglect of regional cinema within feminist and queer discourse. By rigorously applying feminist theory, including the works of Judith Butler and Laura Mulvey, alongside Antonio Gramsci's theory of cultural hegemony, this study demonstrates how these films subvert dominant narratives of gender and sexuality. Moreover, it expands the scope of regional cinema's contribution to the discourse on intersectionality, agency, and resistance, providing new methodologies for understanding the socio-political implications of Assamese cinema. This paper, therefore, serves to elevate the discourse by positioning Village Rockstar and Bulbul Can Sing as vital cultural texts that interrogate, disrupt, and reframe the historical silencing of marginalized voices in both cinema and society. Through this critical intervention, the research not only contributes to existing knowledge but also pioneers a feminist and queer reading of contemporary Assamese cinema, marking a pivotal academic advancement in the field.

II

In Village Rockstar (2017)9, directed by Rima Das, the narrative revolves around Dhunu, a spirited young girl living in a rural Assamese village, whose dream of owning a guitar and forming a rock band drives much of the story. The film, while seemingly simple in its portrayal of village life, presents a nuanced and critical exploration of the position of women within a patriarchal society, emphasizing both their struggles and resilience.

Dhunu’s character is at the heart of the film’s feminist critique, as she embodies a quiet rebellion against deeply entrenched gender norms. From the outset, Dhunu is presented as a girl who dares to dream beyond the traditional expectations placed upon her gender. Her aspiration to own a guitar and join a rock band, pursuits typically associated with masculinity, symbolizes her defiance of the societal constraints that seek to limit her ambitions. In a community where girls are expected to adhere to traditional roles, her desire to step outside these boundaries positions her as a figure of resistance. Dhunu’s rejection of feminine stereotypes can be critically examined through Judith Butler’s theory of gender performativity, where she disrupts the repetitive societal acts that enforce gender norms. Her pursuit of music is not merely a personal aspiration; it is a political act that challenges the expected performance of femininity in her community.

However, this pursuit is not without obstacles, as Dhunu’s world is shaped by the patriarchal expectations of her community. The film subtly critiques these norms, particularly in how it portrays the limited opportunities available to women. Dhunu’s mother, a widow, is a key figure in this critique. Her character is representative of the many rural women who, despite shouldering immense responsibilities, are bound by societal constraints. As the sole provider for her family, she bears the economic burden of raising her children, yet remains subservient to the patriarchal order that denies her autonomy and financial security. Her strength lies in her resilience, but this resilience is framed within a system that devalues her labor and denies her the freedom to imagine a different life for herself or her children.

The film’s portrayal of Dhunu’s mother aligns with Gayatri Spivak’s concept of the "subaltern," where women like her exist on the margins of society, their voices suppressed by both economic and gendered oppression. Her struggles illustrate how rural women are not only burdened by economic hardship but also by the expectations of a patriarchal society that limits their agency. While she supports Dhunu’s dreams, her own life is shaped by the necessity of survival within a system that offers little room for escape or self-expression. This positioning of Dhunu’s mother invites a critical examination of how economic and gendered oppression intersect in the lives of rural women, making them doubly marginalized in both public and private spheres.

Furthermore, the film captures the lived realities of rural women through its depiction of their daily labor. Women in Dhunu’s village are shown engaged in both domestic work and field labour, highlighting the double burden they carry. The film underscores the physical and emotional toll of this labor, presenting a raw and unembellished view of the economic contributions of women, which are often overlooked or undervalued in patriarchal societies. These women, despite their essential role in sustaining the family, are largely invisible within the power structures of their community. This depiction can be understood through a Marxist feminist lens, which critiques the economic exploitation of women’s labor in both domestic and productive spheres. In Village Rockstar, the women’s labor is essential for the survival of their families, yet it is unrecognized and uncompensated, reinforcing their subordinate position within both the household and society at large.

At the same time, the film offers moments of female solidarity, particularly in the relationship between Dhunu and her mother. Their bond serves as a form of resistance to the patriarchal structures that seek to confine them. Though Dhunu’s mother is bound by societal norms, she quietly supports her daughter’s defiance of these norms. This mother-daughter relationship is a central element of the film’s feminist narrative, as it highlights how women find strength and resilience through their connections with one another. Bell hooks’ concept of "oppositional gaze" can be applied here, as the film invites the audience to view this relationship not as one of mere survival, but as a subtle form of resistance against a patriarchal system that seeks to suppress both women’s aspirations and their emotional bonds. The solidarity between Dhunu and her mother represents a counter-narrative to the individualism often glorified in mainstream cinema, instead emphasizing collective strength as a means of navigating oppression.

In terms of visual representation, Village Rockstar is notable for its rejection of the male gaze. The camera does not objectify Dhunu or the other women in the film, but instead centres their experiences and perspectives. The cinematography captures the landscape through Dhunu’s eyes, immersing the viewer in her world. This approach stands in contrast to the traditional cinematic gaze, which Laura Mulvey critiques as inherently voyeuristic and male-centric. By avoiding objectification, Rima Das crafts a feminist visual narrative that prioritizes the subjectivity of its female characters. The film’s intimate, observational style invites the audience to engage with the characters on their own terms, rather than through the lens of male desire or dominance. This feminist approach to visual storytelling reinforces the film’s thematic focus on women’s agency and subjectivity.

Another critical aspect of the film is its exploration of the intersection of class and gender. Dhunu’s dreams are not only constrained by her gender but also by her family’s economic situation. The film offers a pointed critique of how poverty and patriarchy combine to limit the aspirations of young girls in rural India. Dhunu’s desire for a guitar is emblematic of this struggle, as her family’s economic limitations make even this modest dream seem unattainable. This intersection of gender and class reflects Kimberlé Crenshaw’s concept of intersectionality, which highlights how multiple forms of oppression—here, economic deprivation and patriarchal norms—interact to further marginalize individuals. Dhunu’s struggle is not merely one of breaking free from gendered expectations; it is also a fight against the economic conditions that reinforce those expectations. The film thus invites a broader critique of the systemic inequalities that shape the lives of women in rural India, where poverty and patriarchy work in tandem to limit their opportunities for self-expression and empowerment.

While Village Rockstar primarily addresses the challenges young women face in breaking free from traditional gender roles and societal constraints, Bulbul Can Sing takes these explorations a step further by delving into the complexities of adolescence, sexuality, and the additional layer of pressure that comes from societal policing of both female and queer identities. Both films are set in rural Assam, where patriarchal norms are deeply embedded in everyday life, but where Village Rockstar centres on the individual dreams and aspirations of its protagonist, Bulbul Can Sing examines the devastating consequences of stepping outside the accepted boundaries of femininity and sexual behaviour. By focusing on different but overlapping dimensions of gender and social expectation, these two films complement one another, offering a more nuanced picture of how patriarchy affects not only women but also those who deviate from heterosexual norms. The transition from Dhunu’s dream-chasing in Village Rockstar to Bulbul’s more fraught, introspective journey in Bulbul Can Sing allows for a deeper critique of the ways in which rural societies police both gender and sexuality.

Bulbul Can Sing (2018)10, also directed by Rima Das, is a poignant exploration of adolescence, sexuality, and the burdens placed on women and non-conforming individuals in a rural Assamese village. While the narrative centres on Bulbul, a young girl on the cusp of adulthood, the film subtly engages with deeper feminist and queer themes, providing a critique of the societal norms that stifle both female and LGBTQ+ identities. The film invites us to examine how patriarchal control over women’s bodies and sexualities intersects with the marginalization of non-heteronormative expressions of identity, creating a layered and complex portrayal of rural life.

At the heart of the film is Bulbul’s struggle to navigate her desires and identity within a deeply patriarchal society that expects conformity. From the very beginning, we see how the community enforces rigid gender norms that dictate how girls should behave. Bulbul and her friends, particularly Bonny, experience the oppressive weight of societal expectations that closely monitor their interactions with boys, reinforcing the idea that a girl’s value is tied to her sexual purity. Bonny’s relationship with a boy is viewed as a transgression against these norms, and the community’s harsh reaction to her behaviour exposes the extent to which patriarchal control is exercised over women’s bodies.

Bulbul’s own journey is marked by a quiet internal rebellion against these norms. While she does not overtly defy the expectations placed upon her, her hesitance to conform to traditional femininity is evident throughout the film. This reluctance is particularly pronounced in her discomfort with being objectified by the male gaze, as seen when she participates in a local singing competition. The community’s obsession with policing women’s appearances and behaviour is suffocating, and Bulbul’s discomfort serves as a subtle critique of the way in which women are reduced to objects of scrutiny. This speaks to Simone de Beauvoir’s argument in The Second Sex that women’s subjectivity is denied within patriarchal structures, and instead, they are treated as the “other”11 in relation to men’s active subjecthood.

Bulbul’s relationship with Sumu, a sensitive and non-conforming boy, adds a significant queer dimension to the film’s exploration of gender and sexuality. While Sumu’s queerness is never explicitly addressed, it is implied through his effeminate behaviour and the ridicule he faces from others in the village. His non-conformance to traditional masculinity makes him a target of mockery and exclusion, highlighting the rigid gender binaries that dominate the community’s understanding of identity. Sumu’s struggles mirror Bulbul’s own, as both characters face the oppressive weight of societal expectations that seek to define their identities in narrow, restrictive ways. In this sense, the film suggests that both women and queer individuals are similarly constrained by patriarchal norms that seek to regulate their behaviour and suppress their desires.

Judith Butler’s theory of performativity is particularly relevant in understanding Sumu’s marginalization. Butler argues that gender is not an innate identity but rather a series of performative acts that are enforced through social norms. Sumu’s failure to adequately perform masculinity, as defined by the rural community, results in his ostracization. The community’s reaction to Sumu can be seen as a form of gender policing, where those who do not conform to normative gender roles are punished or excluded. This reflects a broader societal anxiety about deviations from heteronormative masculinity, where any failure to adhere to these norms is perceived as a threat to the established social order. Bulbul and Sumu’s friendship are a crucial element of the film, offering a subtle yet profound critique of the ways in which patriarchal and heteronormative structures marginalize those who do not fit neatly into prescribed roles. Their bond represents a form of solidarity that transcends traditional gender and sexual identities, suggesting that those who exist on the fringes of society can find strength in their shared experiences of marginalization. This relationship, though platonic, challenges the conventional narratives of romantic or sexual relationships that dominate cinema, instead presenting an alternative form of kinship that is based on mutual understanding and support.

The tragedy that befalls Bonny is perhaps the most devastating critique of the patriarchal control over women’s bodies and sexualities. Bonny’s death, following the public shaming she endures for engaging in a romantic relationship, is a stark reminder of how rural societies often punish women for expressing their sexuality. The violence directed at her is not merely physical but symbolic, as it represents the community’s need to maintain control over female bodies in order to uphold a fragile moral order. Bonny’s death can be understood through Michel Foucault’s concept of biopower, where the state—or in this case, the community—exerts control over individuals’ bodies to regulate behaviour and maintain social cohesion. The community’s treatment of Bonny reflects the way in which women’s sexualities are policed, with severe consequences for those who deviate from accepted norms.

The portrayal of female sexuality in Bulbul Can Sing is deeply tied to the idea of honour, a concept that is often used to justify the control of women’s bodies in patriarchal societies. Women are burdened with the responsibility of upholding family honour, and any perceived transgression, such as engaging in premarital sexual relationships, is seen as a stain on both their individual reputations and the collective honour of their families. This control over women’s sexuality can be understood through a feminist critique of how patriarchal systems use the concept of honour to justify violence against women. The film exposes the hypocrisy of this system, as it is the women who suffer the consequences of societal judgment, while men’s behaviour is often excused or overlooked.

The film also subtly critiques the economic conditions that shape the lives of women in rural communities. Much like in Village Rockstar, women in Bulbul Can Sing are shown engaged in both domestic and productive labor, but their contributions are largely invisible within the larger power structures of the community. The lack of economic independence further reinforces their vulnerability to patriarchal control, as they have little recourse to escape the expectations placed upon them. Bulbul’s mother, for example, represents the many rural women who bear the economic and emotional burden of supporting their families while remaining subject to patriarchal norms that devalue their labor and deny them autonomy.

The visual representation of Bulbul Can Sing is also significant in how it rejects traditional cinematic portrayals of women and queer individuals. Rima Das’s camera never objectifies her characters, instead capturing their interiority and emotional struggles with a quiet, observational style. This aligns with feminist film theorist Laura Mulvey’s critique of the male gaze, where women are often portrayed as passive objects of desire in mainstream cinema. In Bulbul Can Sing, the female characters, particularly Bulbul, are never reduced to objects for the viewer’s gaze. Instead, the camera invites the audience to engage with their inner worlds, allowing them to be seen as complex, fully realized individuals rather than mere objects of spectacle.

Moreover, the film’s visual style reflects the isolation and vulnerability of its characters. The rural landscape, while beautiful, also serves as a backdrop for the harsh realities of life in a patriarchal society. The wide shots of open fields and rivers, juxtaposed with the claustrophobic interiors of homes and classrooms, mirror the tension between freedom and confinement that defines Bulbul’s experience. While the natural world offers moments of solace and escape, the social structures of the village remain ever-present, imposing limits on what she and her friends can achieve or express.

1. Robert A. Rosenstone, Visions of the Past: The Challenge of Film to Our Idea of History, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1995, p. 71.

2. Edward Said, Orientalism, Penguin Press, New Delhi, 2003 “Introduction” to Orientalism, p. 1.

3. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, A Critique of Postcolonial Reason, Harvard University Press, Harvard, 1991, p.274.

4. Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, Penguin Press, London, 1979, p.93.

5. Laura Mulvey, Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, Afterall Books, London, 2016, p.12.

6. Ibid. p.23.

7. bell hooks, black looks race and representation, Routledge, London, 1992, p.115.

8. Judith Butler, Gender Trouble, Routledge, New York, 2010, p.179.

9. Village Rockstar, Dir. Rima Das, Producer Rima Das, 2017.

10. Bulbul Can Sing, Dir. Rima Das, Produced Flying River Films, 2018.

11. Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex, Vintage, London, 2011, p.529.